by

STEPHEN KINZER

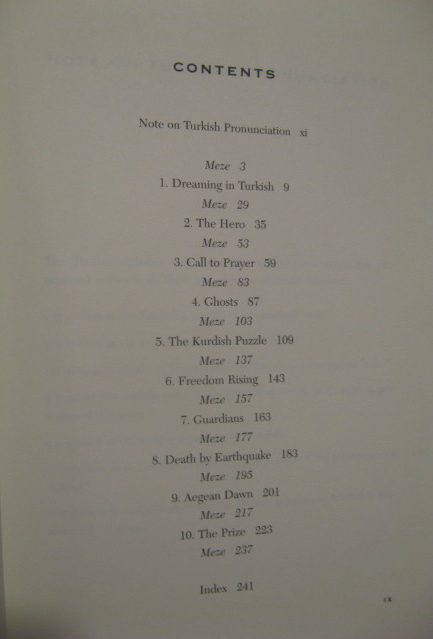

"Crescent and Star: Turkey Between Two Worlds"

by

Stephen Kinzer

272 Pages, Farrar, Straus and Giroux Press, 2001

First Edition

(Hardcover)

| Author: | Stephen Kinzer | Edition: | 1 |

| Publisher: | Farrar Straus & Giroux | ISBN-10: | 0374131430 |

| Subject: | History | ISBN-13: | 9780374131432 |

| Topic: | Europe | Format: | Hardcover |

| Language: | English | Publication Year: | 2001 |

“A sharp, spirited appreciation of where Turkey stands now, and where it may head.” —Carlin Romano, The Philadelphia Inquirer In the first edition of this widely praised book, Stephen Kinzer made the convincing claim that Turkey was the country to watch—poised between Europe and Asia, between the glories of its Ottoman past and its hopes for a democratic future, between the dominance of its army and the needs of its civilian citizens, between its secular expectations and its Muslim traditions. In this newly revised edition, he adds much important new information on the many exciting transformations in Turkey’s government and politics that have kept it in the headlines, and also shows how recent developments in both American and European policies (and not only the war in Iraq) have affected this unique and perplexing nation.

Chicago Tribune - John Maxwell Hamilton:

Kinzer's adventures in Turkey gave him in-depth knowledge and real appreciation for the country and its potential . . .

The Philadelphia Inquirer - Carlin Romano:

A sharp, spirited appreciation of where Turkey stands now, and where it may head.

Richard D. Holbrooke:

In concise and elegant prose, Stephen Kinzer captures the excitement of modern Turkey with all its complexities and ambiguities . . .

Ahmet M. Ertegun:

Kinzer has obviously fallen in love with Turkey and the Turkish people. . . Crescent and Star is a must read.

Robert D. Kaplan:

. . . [Kinzer] shows that good journalism conveys the history and culture of a country . . . The result is an intriguing portrait.

Library Journal:

Americans can no longer plead ignorance about modern Turkey. Recently, several excellent books on the subject have been published by Western journalists: Marvine Howe's Turkey Today (LJ 6/1/00), Nicole and Hugh Pope's Turkey Unveiled (Overlook, 1998), and now this work by Kinzer, former New York Times Istanbul bureau chief (1996-2000). All three are informative and provocative, though each has a slightly different focus (Howe focuses on the role of Islam, while the Popes provide a narrative history). Interspersing journalistic essays with personal vignettes, Kinzer discusses Turkey's potential to be a world leader in the 21st century, as it is truly a bridge between East and West, politically and geographically. Kinzer questions Turkey's ability to achieve this potential, however, unless true democracy can be established. Whether it can depends on Turkey's military, which, in order to ensure the continuation of the Kemalist ideal of a paternalistic state, has never allowed real freedom of speech, press, or assembly. Kinzer argues persuasively that if the military refuses this opportunity, the consequences (Islamic fundamentalism, Kurdish terrorism, denial of EU membership) could be catastrophic for the Turkish state and its people. An excellent, insightful work; highly recommended.

Kirkus Reviews:

A lively, engaging report on modern-day Turkey, a nation poised between democracy and military rule. Kinzer ("Blood of Brothers", 1991), former Istanbul bureau chief for the "New York Times", is unabashed in his enthusiasm for the Turkish people and their rough-edged, yet vibrant, centuries-old society. This quality energizes his consideration of Turkish history as reflected by their 21st-century dilemmas. The Turks were reviled for centuries in Europe due to Ottoman imperialism. Kinzer explores the political paradoxes that followed the Turkish Republic's establishment in 1923 by national hero Kemal Atatürk, whose example created "Kemalism"-essentially the state's secular religion. Atatürk embodied the fiercely guarded, masculine Turkish traditions, but he advocated a "Westernization" of Turkey in civic and social matters. Another paradox lies in the uneasy Turkish dance with democracy, crucial to its acceptance by the European Union, yet repeatedly checked by the nation's skittish and powerful military. Strangely, Turks continue to put their faith in this regime, pointing to the successful 1997 "postmodern coup" against Necmettin Erbakan's Welfare party, which promoted fundamentalist Islamic rule. Yet the military's prominence has been tainted by the Kurdish conflict; Kinzer determines that the Kurdish PKK revolutionary group cynically prodded the army into "scorched-earth" warfare and civilian atrocities, thus damaging Turkey in the court of international opinion. (A similar historical resonance exists in a continued unwillingness to acknowledge the 1915 Armenian genocide.) Kinzer varies his intelligent untangling of these thorny matters with more personalized depictions ofthe Turkish people and the (mostly) good times he's spent among them. These range from their rituals of communal water-pipe smoking and consumption of the powerful liquor raki, to Kinzer's surprise interrogation by rural security forces as a suspected PKK sympathizer. Kinzer's well-executed travelogue addresses the "striking contrast between freedom and repression [that] crystallizes Turkey's conundrum," and will satisfy anyone curious about the future of this vibrant, volatile society.

FROM THE BOOK:

My favorite word in Turkish is istiklal. The dictionary says it means " independence," and that alone is enough to win it a place of honor in any language. It has special resonance in Turkey because Turkey is struggling to become independent of so much. It wants to break away from its autocratic heritage, from its position outside the world's political mainstream, and from the stereotype of the terrifying Turk and the ostracism which that stereotype encourages. Most of all, it is trying to free itself from its fears — fear of freedom, fear of the outside world, fear of itself.

But the real reason I love to hear the word istiklal is because it is the name of Turkeys most fascinating boulevard. Jammed with people all day and late into the night, lined with cafés, bookstores, cinemas and shops of every description, it is the pulsating heart not only of Istanbul but of the Turkish nation. I go there every time I feel myself being overwhelmed by doubts about Turkey. Losing myself in Istiklal's parade of faces and outfits for a few minutes, overhearing snippets of conversation and absorbing the energy that crackles along its mile and a half, is always enough to renew my confidence in Turkey's future. Because Istanbul has attracted millions of migrants from other parts of the country — several hundred new ones still arrive every day — this street is the ultimate melting pot. The country would certainly take a huge leap forward if people could be grabbed there at random and sent to Ankara to replace the members of Parliament. Istiklal is perfectly named because its human panorama reflects Turkey's drive to break away from claustrophobic provincialism and allow its people to express their magnificent diversity.

That drive has been only partly successful. Something about the concept of diversity frightens Turkey's ruling elite. It triggers the deep insecurity that has gripped Turkish rulers ever since the Republic was founded in 1923, an insecurity that today prevents Turkey from taking its proper place in the modem world.

No nation was ever founded with greater revolutionary zeal than the Turkish Republic, nor has any undergone more sweeping change in such a short time. In a very few years after 1923, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk transformed a shattered and bewildered nation into one obsessed with progress. His was a one-man revolution, imposed and steered from above. Atatürk knew that Turks were not ready to break violently with their past, embrace modernity and turn decisively toward the West. He also knew, however, that doing so would be the only way for them to shape a new destiny for themselves and their nation. So he forced them, often over the howling protests of the old order.

The new nation that Atatürk built on the rubble of the Ottoman Empire never could have been built democratically. Probably not a single one of his sweeping reforms would have been approved in a plebiscite. The very idea of a plebiscite, of shaping a political system according to the people's will, would have struck most Turks of that era as not simply alien but ludicrous.

In the generations that have passed since then, Turkey has become an entirely different nation. It is as vigorous and as thirsty for democracy as any on earth. But its leaders, who fancy themselves Atatürk's heirs, fiercely resist change. They believe that Turks cannot yet be trusted with the fate of their nation, that an elite must continue to make all important decisions because the people are not mature enough to do so.

Atatürk's infant Turkish Republic was a very fragile creation. Sheiks and leaders of religious sects considered its commitment to secularism a direct assault on all they had held sacred for centuries. Tribal chieftains and local warlords realized that a strong centralized state would undermine their authority. Kurds who dominated eastern provinces sought to take advantage of the new state's weakness by staging military uprisings. European powers hoped it would collapse so that they could divide its territory among themselves. The new Soviet Union actively sought to subvert it and turn it into a vassal state.

In this hostile climate, Atatürk and his comrades came to think of themselves as righteous crusaders slashing their way through a world filled with enemies. They ruled by decree and with a rubber-stamp Parliament, equating criticism with treason. During their first years in power, arrest and execution were the fate of their real and imagined opponents.

Three-quarters of a century has passed since then, and in that time Turkey has changed beyond recognition. The nation that faced Atatürk when he took power was not only in ruins but truly primitive. Nearly everyone was illiterate. Life expectancy was pitifully short, epidemics were accepted as immutable facts of life and medical care was all but nonexistent. The basic skills of trade, artisanry and engineering were unknown, having vanished with the departed Greeks and Armenians. Almost every citizen was a subsistence farmer. There were only a few short stretches of paved road in a territory that extended more than a thousand miles from Iran to Greece. Most important of all, the Turkish people knew nothing but obedience. They had been taught since time immemorial that authority is something distant and irresistible, and that the role of the individual in society is submission and nothing more.

If Atatürk could return to see what has become of his nation, he undoubtedly would be astonished at how far it has come. Muddy villages have become bustling cities and cow paths have become superhighways. Universities and public hospitals are to be found in even the most remote regions. The economy is unsteady but shows bursts of vitality. Turkish corporations and business conglomerates are making huge amounts of money and competing successfully in every corner of the globe. Hundreds of young men and women return home every year from periods of study abroad. People are educated, self-confident and eager to build a nation that embodies the ideals of democracy and human rights.

The ruling elite, however, refuses to embrace this new nation or even admit that it exists. Military commanders, prosecutors, security officers, narrow-minded bureaucrats, lapdog newspaper editors, rigidly conservative politicians and other members of this sclerotic cadre remain psychologically trapped in the 1920s. They see threats from across every one of Turkey's eight borders and, most dangerously, from within the country itself. In their minds Turkey is still a nation under siege. To protect it from mortal danger, they feel obliged to run it themselves. They not only ignore but actively resist intensifying pressure from educated, worldly Turks who want their country to break free of its shackles and complete its march toward the democracy that was Atatürk's dream.

This dissonance, this clash between what the entrenched elite wants and what more and more Turks want, is the central fact of life in modern Turkey. It frames the country's great national dilemma. Until this dilemma is somehow resolved, Turkey will live in eternal limbo, a half-democracy taking half-steps toward freedom and fulfilling only half its destiny.

The most extraordinary aspect of this confrontation is that both sides are seeking, or claim to be seeking, the same thing: a truly modern Turkey. Military commanders and their civilian allies, especially the appointed prosecutors, judges and governors who set the limits of freedom in every town and province, consider themselves modernity's great and indispensable defenders. They fear democracy not on principle, but because they are convinced it will unleash forces that will drag Turkey back toward ignorance and obscurantism. Allowing Turks to speak, debate and choose freely, they believe, would lead the nation to certain catastrophe. To prevent that catastrophe, they insist on holding ultimate political power themselves and crushing challenges wherever they appear.

Yet what this means in practice is that state power is directed relentlessly against the very forces in society that represent true modernity. Writers, journalists and politicians who criticize the status quo are packed off to prison for what they say and write. Calls for religious freedom are considered subversive attacks on the secular order. Expressions of ethnic or cultural identity are banned for fear that they will trigger separatist movements and ultimately rip the country apart. When foreign leaders remind Turkey that it can never become a full member of the world community as long as its government behaves this way, they are denounced for harboring secret agendas whose ultimate goal is to wipe Turks off the face of history.

These attitudes have turned Turkey's ruling elite into the enemy of the ideal that gave it life. Originally dedicated to freeing a nation from dogma, this elite now defends dogma. Once committed to liberating the mind, today it lashes out against those whose minds lead them to forbidden places. It has become the "sovereign" against which its spiritual ancestors, the Young Turks, began rebelling in the nineteenth century.

"Our sovereign and our government do not want the light to enter our country," the Young Turk theorist Abdullah Cevdet wrote in 1897. "They want all people to remain in ignorance, on the dunghill of misery and wretchedness; no touch of awakening may blaze in the hearts of our compatriots. What the government wants is for the people to remain like beasts, submissive as sheep, fawning and servile as dogs. Let them hear no word of any honest lofty idea. Instead, let them languish under the whips of ignorant gendarmes, under the aggression of shameless, boorish, oppressive officials."

The Young Turks were members of insurgent groups that defied the absolutism of Ottoman rule during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These groups built a rich tradition of dissent that shaped the intellectual and political life of the late Ottoman period and laid the foundation for Atatürk's revolution. Their principles were admirable, but most of their leaders believed instinctively that the state, not popular will, was the instrument by which social and political change would be achieved. They bequeathed to Atatürk the conviction that Turkish reformers should seize state power and then use it ruthlessly for their own ends, not try to democratize society in ways that would weaken the centralized state.

Foundation For Kurdish Library & Museum