SHANIDAR

The First Flower People

by Ralph Solecki

A fascinating tale of a great cave in the Southern Kurdistan (in the part of Kurdistan occupied by Iraq) where it is believed that the first ritualized burial of a Neanderthal took place. Paleobotanists discovered enormous quantities of pollen about the excavated bodies, leading them to believe that the corpses were left with flowers, and purposely buried with a care previously unseen in fossilized human remains.

FIRST EDITION 1971 Illustratedd with numerous photos, diagrams and 3 maps. 280 pages, w/biblio, index.

The Skull Of Shanidar II. Written by T.D. Stewart, published in 1962 by the Smithsonian Institution. Illustrated.

Shanidar Cave is an archaeological site in the Bradost mountain, Zagros Mountains in Hawler Governorate, Southern Kurdistan "Iraq". The site is located in the valley of the Great Zab. It was excavated from 1957–1961 by Ralph Solecki and his team from Columbia University and yielded the first adult "Neanderthal skeletons in Iraq", dating from 60–80,000 years BP.

The excavated area produced nine skeletons of Neanderthals of varying ages and states of preservation and completeness (labelled Shanidar I – IX). The tenth individual was recently discovered by M. Zeder during examination of a faunal assemblage from the site at the Smithsonian Institution. The remains seemed to Zeder to suggest that Neandertals had funeral ceremonies, burying their dead with flowers (although the flowers are now thought to be a modern contaminant), and that they took care of injured individuals. One skeleton and casts of the others at the Smithsonian Institution are all that is left of the findings, the originals having been dispersed in Iraq.

Berhemeka din a lêkolînî ya bi navê: Goristana

ji Serdema Kevirî ya Pêşî Li Şikefta Şanîdarê

The Proto Neolithic Cemetery ku ji hêla Ralph S. Solecki, Rose E.

Solecki & Anagnostis P. Agelarakis'î ve hatiye nivîsîn

New Excavations at Shanidar

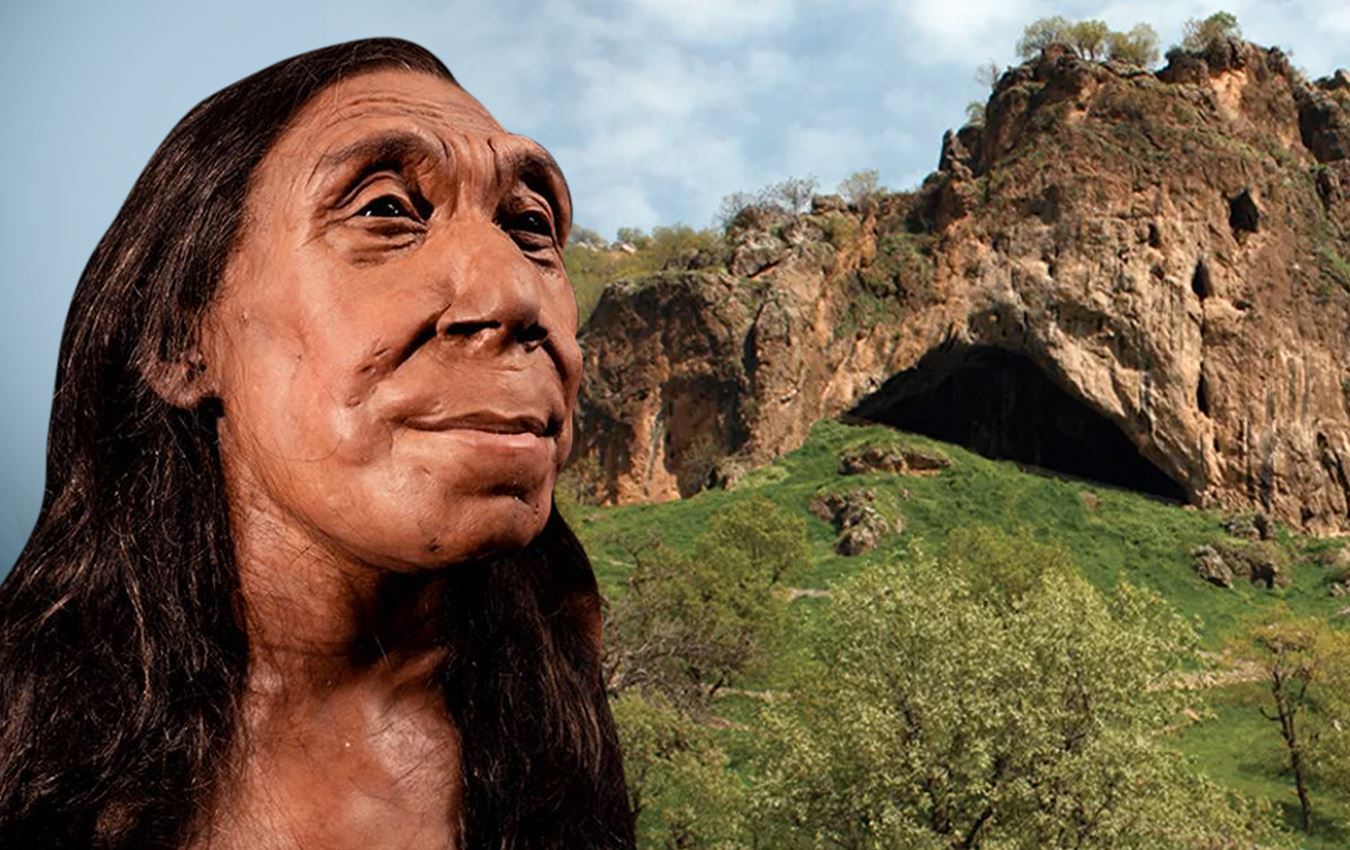

İlkel kafatası'nın yeniden inşası sonra elde edilen sonuç

Yaklaşık 60,000 yıl önce Güney Kürdistan'daki dünyaca meşhur Şanidar Mağarası'nda gömülü olan "yaşlı adam" büyük olasılıkla bir gözü kör oldu ve ölümünden çok önce bir kolunu kaybetti. Buna rağmen 50 yıl ya da daha fazla yaşadı. Kafası, sanatçı Kathleen Gallo tarafından modern adli tıp teknikleri kullanılarak yeniden inşa edildi.

It was discovered in the Şanidar Cave on Bradost Mountain in Southern Kurdistan. The funeral is from the Middle Paleotik the date of 90.000 BC.

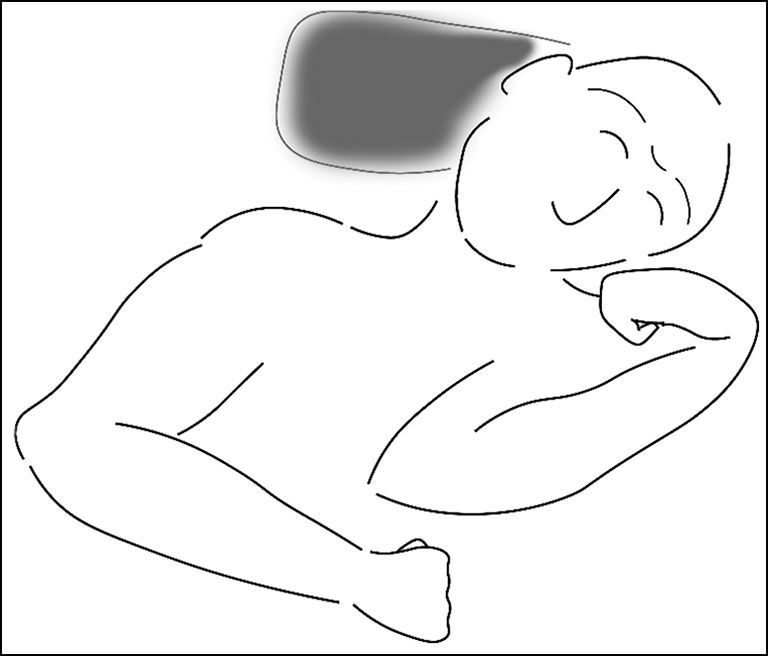

He is replaced with a special ceremony in the birth position. The picture is a realistic rekonstruction. In archeology, such drawings are used abundantly,

so called reconstruction.

Dünyada cenazeyi çiçekle gömmenin en eski adeti, Güney Kürdistan'ın Bradost Dağı’ndaki Şanidar Mağarasında bulunmuştur. Cenaze Orta

Paleotik’te MÖ. 90.000 tarihine denk gelmektedir.

Burada bu cenaze özel bir törenle anne karnında doğduğu pozisyonda yatırılmıştır

Fotoğraf gerçeğin birebir çizimdir. Arkeoloji’de bu tarz çizimler bolca kullanılmaktadır. Buna rekonstrüksiyon da denmektedir.

Kürdistan'daki yaşamın insanlık ve medeniyet kökü işte bu kadar derindir

This crushed Neanderthal skull was unearthed last fall at Shanidar cave in Iraqi Kurdistan,

right next to the flower burial excavated in the 1950s.

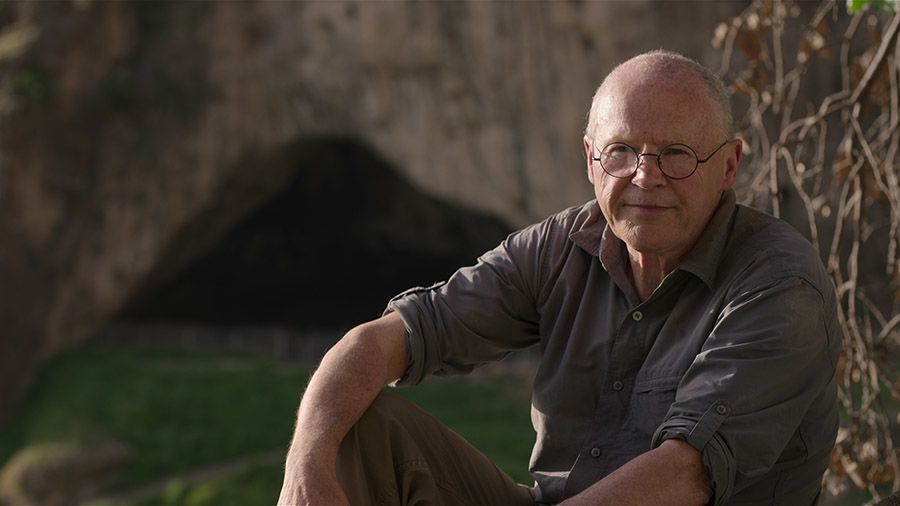

GRAEME BARKER

Burada ne gördüğünüzü tam olarak çıkaramıyor musunuz?

Yakından bak.

Bu aslında bin yıllık tortu ve düşen kayalar tarafından sıkıştırılmış bir Neandertal'in yassı kafatasıdır.

Kafatası, 2017 yılında Kürdistantaki Shanidar Mağarası'nda bir araştırmacı ekibi tarafından ortaya çıkarılan bir iskeletin parçasıydı - bölgede 10 diğer Neandertalin iskelet kalıntılarının bulunmasından yarım yüzyıldan fazla bir süre sonra.

Bu ilk bulgular bilim adamlarına eski atalarımızın nasıl yaşadıklarına dair nadir bir bakış. Buluntular arasında: Arkeologların Neandertallerin ölülerinin üzerine çiçek koymak gibi cenaze törenleri olduğu sonucuna varmasına neden olan cesetlerin yakınındaki polenler.

Şimdi araştırmacılar, kalıntılarla birlikte yerleştirilmiş kayaları tanımlamak için modern arkeolojik teknikleri kullandılar ve bu yeni bulgunun, kasıtlı olarak gömülen birinin başka bir örneği olduğunu gösterdi.

Graeme Barker, Cambridge Üniversitesi

Arkeologlar Güney Kurdistan'ın Hewler vilayetinde bulunan Şanidar mağarasında Neandertal ait iki farklı insan kemiği buldu. |

|

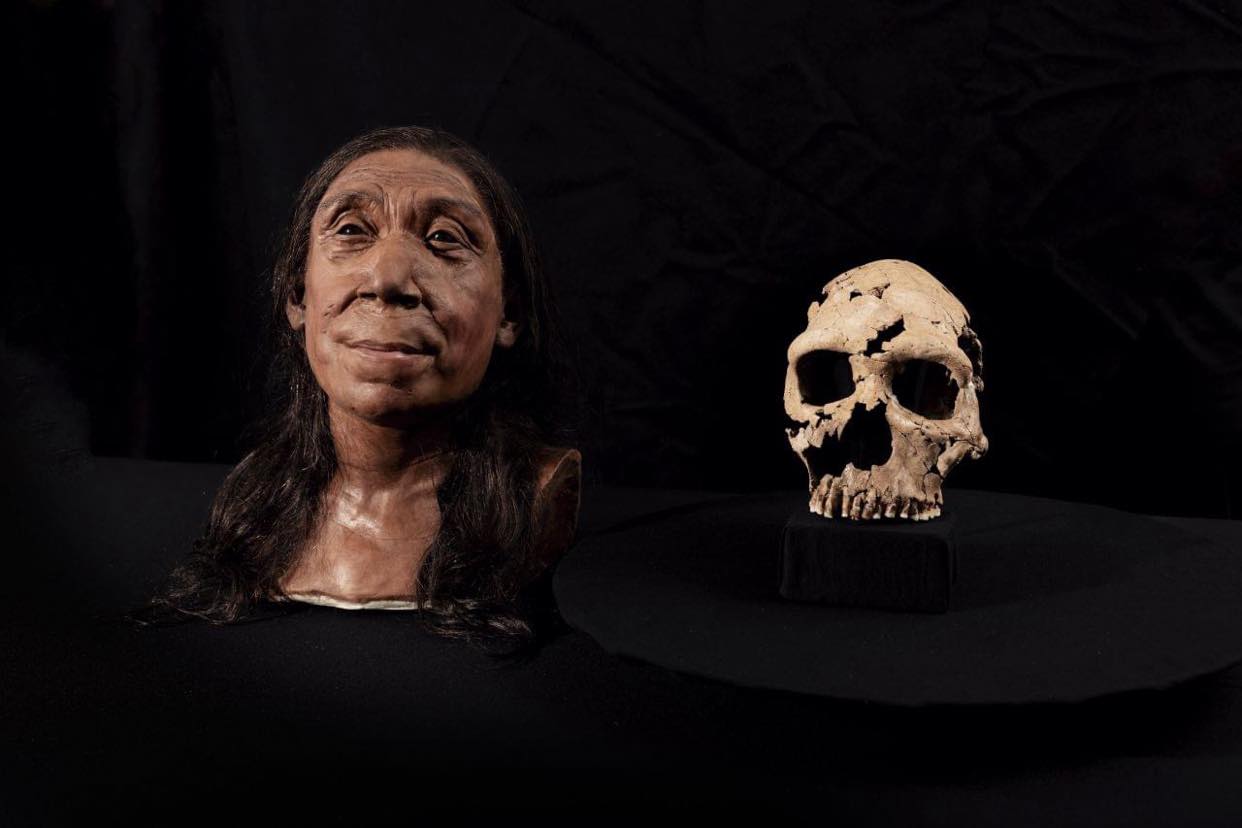

The 75,000-year-old skull reconstructed

It was

found in the famous cave of Shanidar in Kurdistan

A team from Cambridge Archaeology discovered a flattened Neanderthal skull in a famous cave of Shanidar where the enigmatic species repeatedly returned to bury their dead. The team painstakingly reconstructed the 75,000-year-old skull from hundreds of ancient bone fragments the consistency of biscuit dunked in tea. The reformed skull was used to recreate the Neanderthal womans head, now unveiled in a new Netflix documentary![]() Explore the world of Shanidar Z

Explore the world of Shanidar Z ![]() https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/shanidar-z-face-revealed?utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook

https://www.cam.ac.uk/stories/shanidar-z-face-revealed?utm_medium=social&utm_source=facebook ![]() Secrets of the Neanderthals/Netflix; BBC Studios/Jamie Simonds; Graeme Barker. 01.05.2024

Secrets of the Neanderthals/Netflix; BBC Studios/Jamie Simonds; Graeme Barker. 01.05.2024

Dr Emma Pomeroy with the skull of Shanidar Z in the Henry Wellcome Building in Cambridge, home of the Universitys Leverhulme Centre for Human Evolutionary Studies.

The skull of Shanidar Z, flattened by thousands of years of sediment and rock fall, in situ in Shanidar Cave, Iraqi Kurdistan. Credit: Graeme Barker.

The skull of Shanidar Z, which has been reconstructed in the lab at the University of Cambridge. Credit: BBC Studios/Jamie Simonds

The team excavated the female Neanderthal in 2018 from inside a cave in Southern ('Iraqi') Kurdistan where the species had repeatedly returned to lay their dead to rest.

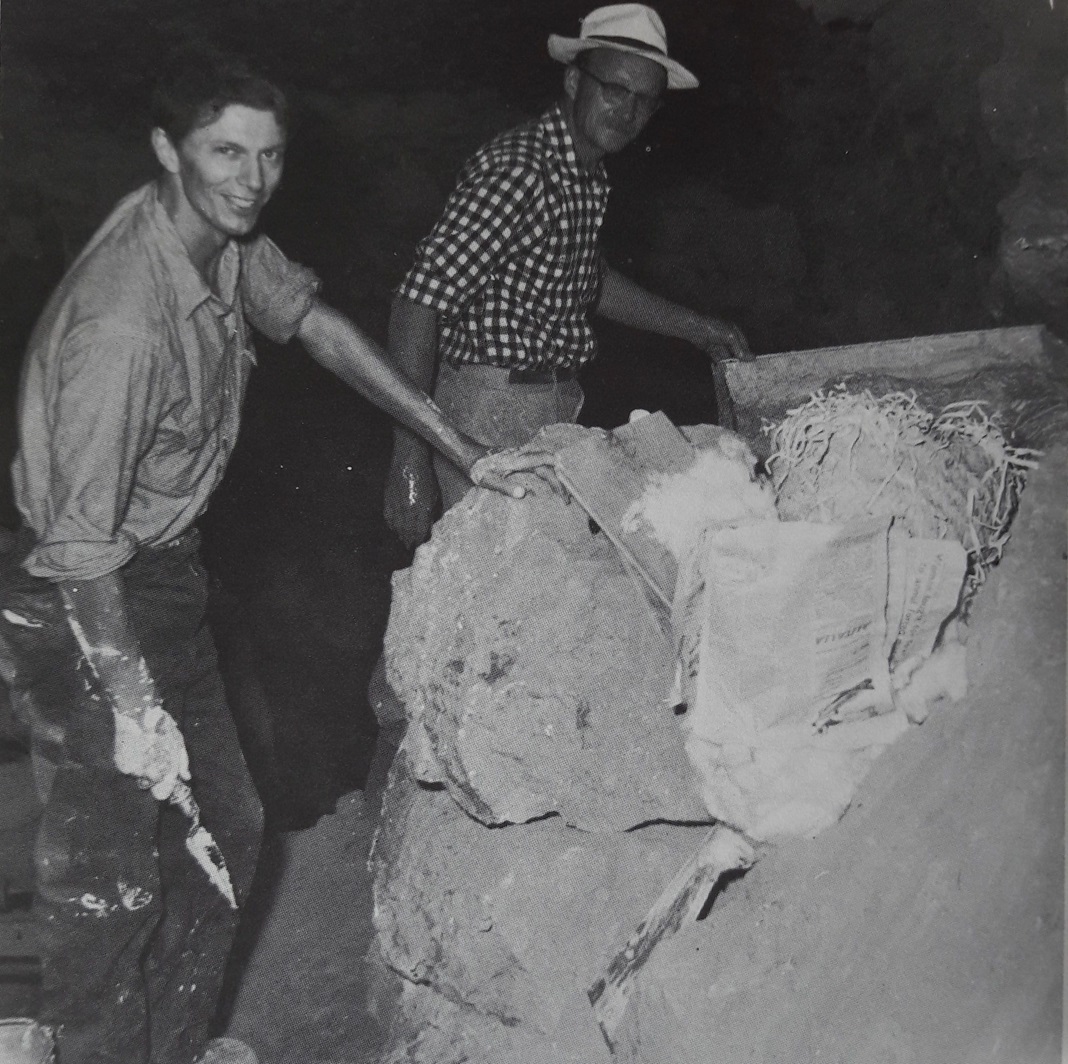

The cave was made famous by work in the late 1950s that unearthed several Neanderthals which appeared to have been buried in succession.

Secrets of the Neanderthals, produced by BBC Studios Science Unit, is released on Netflix worldwide. The documentary follows the team led by the universities of Cambridge and Liverpool John Moores as they return to Shanidar Cave to continue excavations.

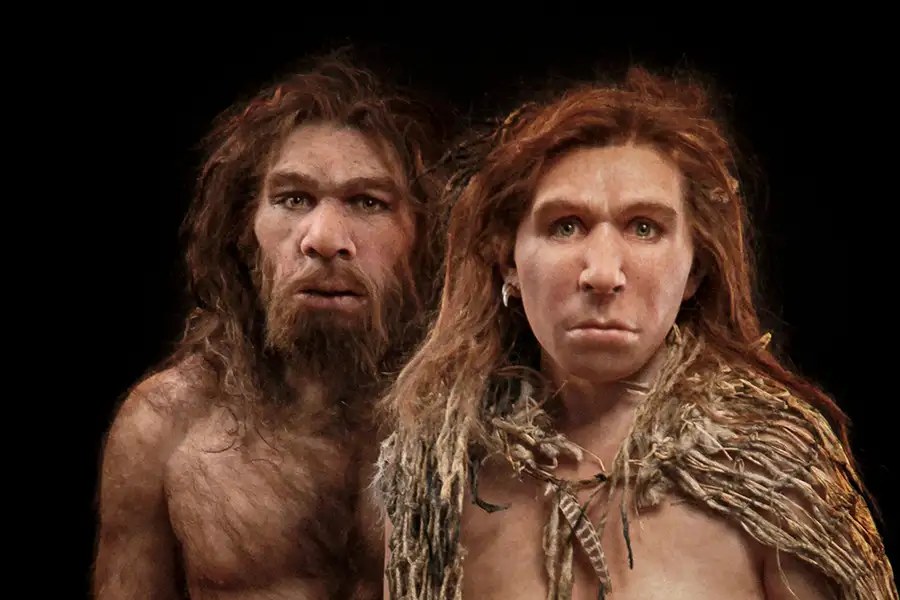

The skulls of Neanderthals and humans look very different, said Dr Emma Pomeroy, a palaeo-anthropologist from Cambridges Department of Archaeology, who features in the new film.

Neanderthal skulls have huge brow ridges and lack chins, with a projecting midface that results in more prominent noses. But the recreated face suggests those differences were not so stark in life.

Its perhaps easier to see how interbreeding occurred between our species, to the extent that almost everyone alive today still has Neanderthal DNA.

Neanderthals are thought to have died out around 40,000 years ago, and the discoveries of new remains are few and far between. The Neanderthal featured in the documentary is the first from the cave for over fifty years, and perhaps the best preserved individual to be found this century.

While earlier finds were numbered, this one is called Shanidar Z, although researchers think it may be the top half of an individual excavated in 1960.

The head had been crushed, possibly by rockfall, relatively soon after death after the brain decomposed but before the cranium filled with dirt and then compacted further by tens of thousands of years of sediment.

When archaeologists found it, the skull was flattened to around two centimetres thick.

The team carefully exposed the remains, including an articulated skeleton almost to the waist, and used a glue-like consolidant to strengthen the bones and surrounding sediment. They removed Shanidar Z in dozens of small foil-wrapped blocks from under seven and a half metres of soil and rock within the heart of the cave.

In the Cambridge lab, researchers took micro-CT scans of each block before gradually diluting the glue and using the scans to guide extraction of bone fragments.

Lead conservator Dr Lucía López-Polín pieced over 200 bits of skull together freehand to return it to its original shape, including upper and lower jaws.

Each skull fragment is gently cleaned while glue and consolidant are re-added to stabilise the bone, which can be very soft, similar in consistency to a biscuit dunked in tea, said Pomeroy.

Its like a high stakes 3D jigsaw puzzle. A single block can take over a fortnight to process.

The team even referred to forensic science studies on how bones shift after blunt force trauma and during decomposition to help them understand if remains had been buried, and the ways in which teeth had pinged from jawbones.

The rebuilt skull was surface scanned and 3D-printed, forming the basis of a reconstructed head created by world-leading palaeoartists and identical twins Adrie and Alfons Kennis, who built up layers of fabricated muscle and skin to reveal a face.

New analysis strongly suggests that Shanidar Z was an older female, perhaps in her mid-forties according to researchers a significant age to reach so deep in prehistory.

Without pelvic bones, the team relied on sequencing tooth enamel proteins to determine her sex. Teeth were also used to gauge her age through levels of wear and tear with some front teeth worn down to the root.

At around five feet tall, and with some of the smallest adult arm bones in the Neanderthal fossil record, her physique also implies a female.

While remnants of at least ten separate Neanderthals have now come from the cave, Shanidar Z is the fifth to be found in a cluster of bodies buried at a similar time in the same location: right behind a huge vertical rock, over two metres tall at the time, which sits in the centre of the cave.

The rock had come down from the ceiling long before the bodies were interred. Researchers say it may have served as a landmark for Neanderthals to identify a particular site for repeated burials.

Neanderthals have had a bad press ever since the first ones were found over 150 years ago, said Professor Graeme Barker from Cambridges McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, who leads the excavations at the cave.

Our discoveries show that the Shanidar Neanderthals may have been thinking about death and its aftermath in ways not so very different from their closest evolutionary cousins ourselves.

The other four bodies in the cluster were discovered by archaeologist Ralph Solecki in 1960. One was surrounded by clumps of ancient pollen. Solecki and pollen specialist Arlette Leroi-Gourhan argued the finds were evidence of funerary rituals where the deceased was laid to rest on a bed of flowers.

This archaeological work was among the first to suggest Neanderthals were far more sophisticated than the primitive creatures many had assumed, based on their stocky frames and ape-like brows.

Members of Ralph Soleckis team, Dr T. Dale Stewart (right) and Jacques Bordaz (left) at Shanidar Cave in 1960, working on removing the remains of Shanidar 4 (the flower burial). Credit: Ralph Solecki

Decades later, the Cambridge-led team retraced Soleckis dig, aiming to use the latest techniques to retrieve more evidence for his contentious claims, as well as the environment and activities of the Neanderthals and later modern humans who lived there, when they uncovered Shanidar Z.

Shanidar Cave was used first by Neanderthals and then by our own species, so it provides an ideal laboratory to tackle one of the biggest questions of human evolution, said Barker.

Why did Neanderthals disappear from the stage around the same time as Homo sapiens spread over regions where Neanderthals had lived successfully for almost half a million years?

Professor Graeme Barker from the University of Cambridge, who leads the current Shanidar cave excavations. Credit: Netflix

A study led by Professor Chris Hunt of Liverpool John Moores University now suggests the pollen was left by bees burrowing into the cave floor. However, remains from Shanidar Cave still show signs of an empathetic species. For example, one male had a paralysed arm, deafness and head trauma that likely rendered him partially blind, yet had lived a long time, so must have been cared for.

Site analysis suggests that Shanidar Z was laid to rest in a gully formed by running water that had been further hollowed out by hand to accommodate the body.

Posture indicates she had been leant against the side, with her left hand curled under her head, and a rock behind the head like a small cushion, which may have been placed there.

Illustration of the possible burial position of the new Neanderthal remains from Shanidar Cave. Credit: Emma Pomeroy.

While Shanidar Z was buried within a similar timeframe as other bodies in the cluster, researchers cannot say how contemporaneous they are, only that they all date to around 75,000 years ago.

In fact, while filming onsite for the new documentary in 2022, the team found remains of yet another individual in the same burial cluster, uncovering the left shoulder blade, some ribs and a fairly complete right hand.

In the sediments several feet above, another three Neanderthals dating to around 50,000 years had been found by Solecki, more of which have been recovered by the current team.

Further research since Shanidar Z was found has detected microscopic traces of charred food in the soil around the older body cluster. These carbonised bits of wild seeds, nuts and grasses, suggest not only that Neanderthals prepared food soaking and pounding pulses and then cooked it, but did so in the presence of their dead.

The body of Shanidar Z was within arms reach of living individuals cooking with fire and eating, said Pomeroy. For these Neanderthals, there does not appear to be that clear separation between life and death.

We can see that Neanderthals are coming back to one particular spot to bury their dead. This could be decades or even thousands of years apart. Is it just a coincidence, or is it intentional, and if so what brings them back?

As an older female, Shanidar Z would have been a repository of knowledge for her group, and here we are seventy-five thousand years later, learning from her still, Pomeroy said.

__________________________

The face of a 75,000-year-old Neanderthal woman has been recreated by a team of archeologists from the University of Cambridge after they excavated her body in 2018.

The rare discovery of the Neanderthal skull came from an Iraqi Kurdistan cave where the species was known to lay their dead to rest. The site could indicate how Neanderthals may have been more caring and emotionally intelligent than previously thought.

The team found the Neanderthal named Shanidar Z inside a cave in Iraqi Kurdistan, which is a mountainous region in northern Iraq. The Neanderthal species repeatedly returned to Iraqi Kurdistan to bury their dead, according to the University of Cambridge's findings.

The cave became famous because of several Neanderthals being unearthed there in the late 1950s after their bodies appeared to have been buried in succession, the school in Cambridge, England, said.

Neanderthals are believed to have died out more than 40,000 years ago, making discoveries of new remains "few and far between," according to Cambridge.

Emma Pomeroy, a palaeo-anthropologist from Cambridges Department of Archaeology, says "The skulls of Neanderthals and humans look very different."

Neanderthal skulls have huge brow ridges and lack chins, with a projecting midface that results in more prominent noses," Pomeroy said in the release. "But the recreated face suggests those differences were not so stark in life."

Neanderthal skulls differing from humans could indicate that interbreeding occurred between our species thousands of years ago, Pomeroy said. If true, then "almost everyone alive today still has Neanderthal DNA.

Analysis of Shanidar's remains suggests she was a 5-foot woman who was possibly in her mid-40s, Cambridge said. The team determined her sex and age by observing her tooth enamel and physique, the school added.

"Some front teeth worn down to the root," according to Cambridge's findings.

The Cambridge team that found Shanidar Z's remains only found the top half of her body, and they believe the lower half was excavated in 1960.

Pictured is the rebuilt skull of a 75,000-year-old Neanderthal woman named Shanidar Z.

In Cambridge's lab, researchers "took micro-CT scans of each block before gradually diluting the glue and using the scans to guide extraction of bone fragments," the school said.

Over 200 bits of Shanidar Z's skull were pieced together by lead conservator Lucía López-Polín to restore it to its original shape according to Cambridge.

Each skull fragment is gently cleaned while glue and consolidant are re-added to stabilize the bone, which can be very soft, similar in consistency to a biscuit dunked in tea, Pomeroy said. Its like a high stakes 3D jigsaw puzzle. A single block can take over a fortnight to process.

Once rebuilt, the Shanidar's skull was surface scanned and 3D printed, which formed "the basis of a reconstructed head" created by paleoartists Adrie and Alfons Kennis, Cambridge said. The identical twins built up layers of fabricated muscle and skin to reveal a face, according to the school.

While inside the cave where Shanidar was excavated, the team noticed a "huge vertical rock" that they believe served as a landmark for Neanderthals to identify a certain site for repeated burials, the school said.

Graeme Barker, a Cambridge professor who led to the cave excavation, said "Neanderthals have had a bad press ever since the first ones were found over 150 years ago."

The way the remains in the cave "show signs of an empathetic species" as Shanidar Z was leaned against her side, with her left hand curled under her head and a rock behind the head acting as a small cushion, the school said. The archeologists believe the rock may been placed there.

Our discoveries show that the Shanidar Neanderthals may have been thinking about death and its aftermath in ways not so very different from their closest evolutionary cousins ourselves," Barker said.

___________________

75.000 yıl önce Kürdistan'ın Bradost dağlarındaki dünya üniversiteleri ve bilim adamları arasında çok meşhur ve hatta hakkında başrolünü Holywood artisti Hanna Daryl'in oynadığı Holywood yapımı bir bilmi olan Şanidar Mağarasında gömülmüş bir

Neandertal kadının yüzü bilim insanları tarafından tekrar oluşturuldu.

Bilim adamları, Şanidar Z adı verilen bu neandertal bireyin kırk yaşlarında bir kadın olduğunu öne sürüyor.

Şanidar Mağarası Kürdistan'ın Hewler ilinde Zagros Dağları içinde, Zap Suyu vadisine yakın bir konumda bulunmaktadır.

Afrika çıkışı sonra insan soyu İLK olarak Kürdistan'dan (Zagroslardan) hem Uzakdoğu'ya ve hemde batıya yayıldılar. Ayrı ırklar ve kavimler bu yayılmadan sonra coğrafik etmenler vasıtasıyla şekillenip oluştu. İnsanların Nuh'un kavmi olduğu efsanevi söylencesi doğru olablildiği gibi, Nuh kavminin kürdler olabileceği rivayetinin de doğru olma ihtimali vardır. Çünkü bu rivayetler durup dururken edilmemiştir, mutlaka dayandıkları somut bir fenomen olmalıdır. Nitekim Nuh tufanı rivayetinin gerçek jeolojik bir vakıa olduğu bilim adamları tarafından ispatlanmıştır bugün.

Professor in the Evolution of Health, Diet and Disease, Emma Pomeroy

SHANIDAR

İnsanlığın çıkış noktalarından biri olan Güney Kürdistan'ın Bradost/Soran mıntıkasındakil Şanidar mağarası.

|

|

Foundation For Kurdish

Library & Museum